Earlier Subahdars or Governors of Awadh (or Oudh, now Uttar Pradesh) had not bothered to reside in their territory since Agra and Delhi were so near. It was Nawab Shuja' al-Daula (1754-75) who fixed a local base in Lucknow, till then a religious rather than political centre, and he constructed the massive fort-cum-palace called the Macchi Bhavan facing the River Gumti. There are good views of this structure in the Daniells' Oriental Scenery, but it was destroyed after the events of 1857-58. Following his defeat in 1764 at the Battle of Buxar and the occupation of his capital by the East India Company's troops, Shuja al-Daula moved further east to Faizabad to be closer to the frontier with British India and he built a new fort. That remained his capital until his death in 1775. His son and successor Asaf al-Daula (1775-97) moved the capital back to Lucknow. During the famine of 1784 he initiated as a measure of famine relief the construction of the Bara Imambara, the Great Imambara, for the holding of Shia rites during Muharram, and there he lies buried. The great hall of the Imambara and the three-domed mosque beside it form one of the grandest Islamic complexes in India.

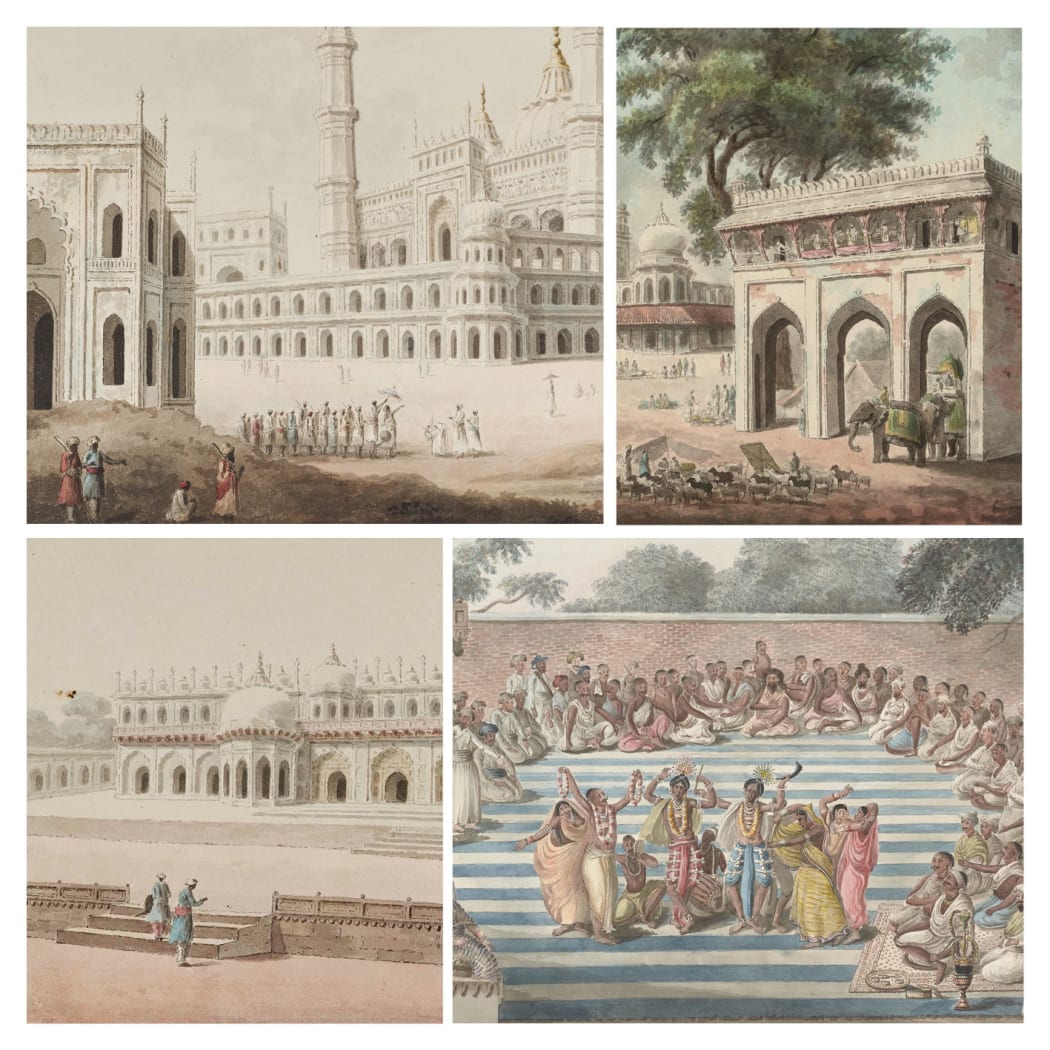

Fig. 1 The Imambara at Lucknow with a visiting dignitary

Murshidabad, possibly by Sita Ram early in his career, c. 1795-1800

After Shuja al-Daula's death, his widow and mother continued to reside at Faizabad and their continued wealth was guaranteed by the East India Company. Unfortunately, Asaf al-Daula fell into arrears of money due to the Company and complained that he was impoverished by the guarantees that had been given to his mother and grandmother. Warren Hastings the Governor-General encouraged him to seize the women's wealth in order to pay the arrears due to the Company, an act which later led to his impeachment in Britain.

During Asaf al-Daula's reign over Awadh, Lucknow became a flourishing centre for the arts and he was by all accounts an insatiable collector. He seems to have been more interested in objects than in paintings, and no artists are known to have definitely been in his patronage, although he did commission portraits from visiting British artists such as Tilly Kettle and Johan Zoffany. He did collect manuscripts including some illustrated manuscripts which had been looted from what was left of the imperial library in Delhi in 1788 by the Rohilla Ghulam Qadir. These manuscripts were given to the retiring Governor General Sir John Shore in 1797-98 who presented them, including the imperial Padshahnama of Shah Jahan, to King George III. Nonetheless, during Asaf al-Daula's reign, numerous artists worked in Lucknow, many of them known by name, who were patronized both by the local nobility and by Europeans such as Jean-Baptiste Gentil, Antoine Polier and Richard Johnson.

The other major power in north India in the later 18th century, the Nawabs of Murshidabad, who were originally the Subahdars of Bengal for the Mughal emperors, likewise came into conflict with the East India Company. Nawab Murshid Quli Khan had in 1704 transferred the capital of Bengal from distant Dacca to Muxadabad on the River Hooghly and renamed the city Murshidabad after himself. He built up a strong power base during his tenure. He lies buried in the half-ruined but still imposing Katra Masjid on the outskirts of the city. Nawab Alivardi Khan (1740-56) seized power from his descendants and was able to keep the Marathas and English East India Company in check. His grandson and successor Siraj al-Daula (1756-57) launched an attack on the Company's Bengal headquarters at Calcutta in 1756 and captured it. The Nawab was defeated and killed the following year when the English retaliated, Clive's victory at Plassey being assured by the defection from the Nawab of the forces of his minister Mir Ja'far. The latter was rewarded by being placed on the masnad or throne himself by Clive, but was henceforth subservient to the Company. His first period of office 1757-60 ended when he was judged not compliant enough by the Company and he was replaced by his son-in-law Mir Qasim, who proved even less so. Another war, into which Shuja al-Daula of Awadh and the exiled Mughal emperor Shah 'Alam were drawn, ended with an English victory at Buxar in 1764. In the meantime, Mir Ja'far had been reinstated on the throne in 1763 but died in 1765. The Treaty of Allahabad that same year gave the Company the Diwani or revenue raising power over the whole of the Subah of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

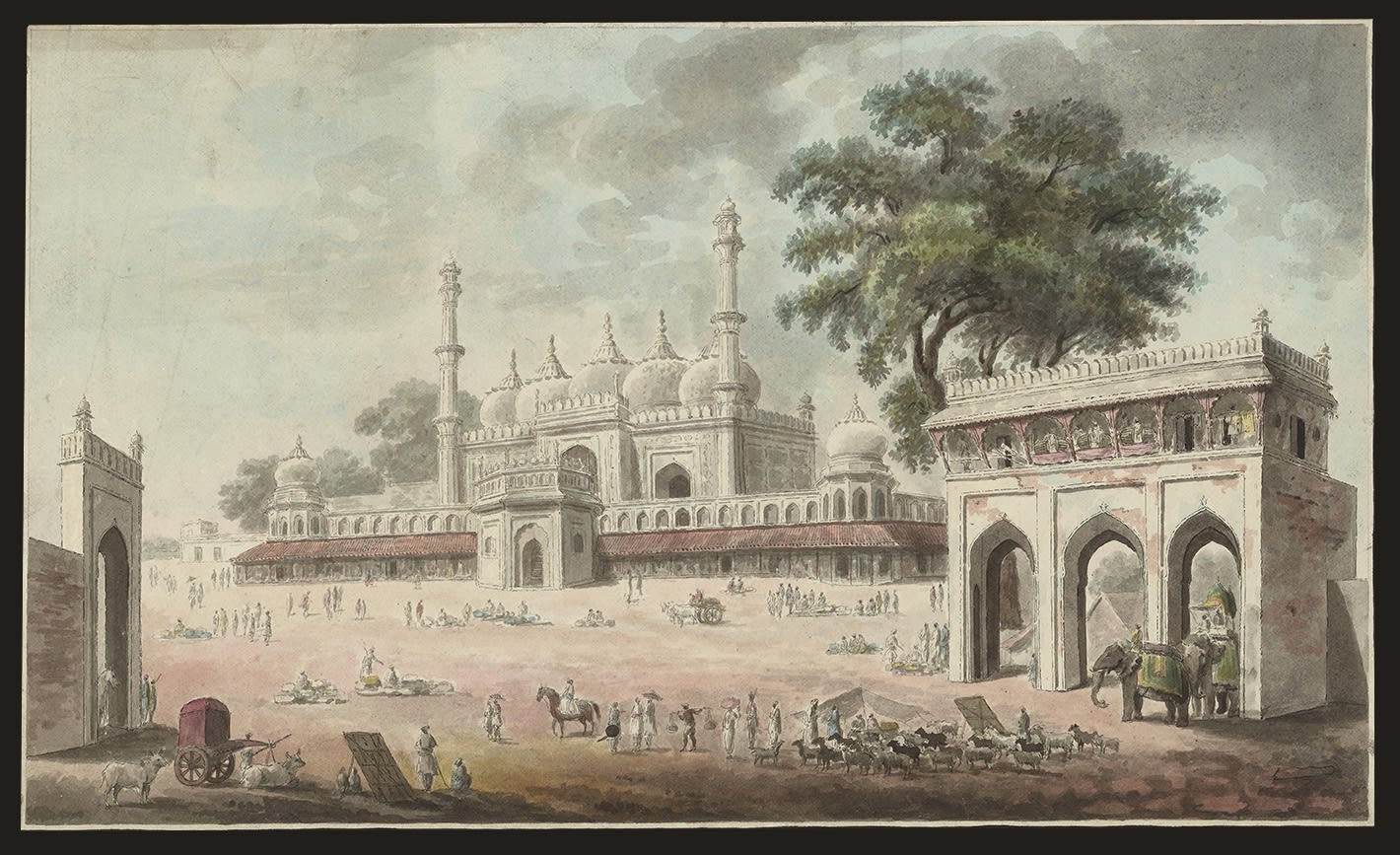

Fig. 2 Munny Begum's mosque and the tripolia gate at Murshidabad with a procession

Munni Begum, originally a dancing girl from Sikandra near Agra, was the second and favourite wife of Mir Ja'far. After his death in 1765, she inherited his vast fortune and immense influence in the palace and in the administration, and was favourably treated by Clive. Her two young sons Najm al-Daula (1765-66) and Saif al-Daula (1766-70) occupied the throne in succession, but her influence was curtailed when her stepson Mubarak al-Daula, born of another wife, came to the throne in 1770. She used her vast wealth to build in 1767 an imposing mosque in the chowkh outside the north gate of the palace (depicted in fig. 2). The mosque has seven bays and five large domes graduated in size, and vaulted colonnades around it, as well as two slender minarets that dominated the old city. The old palace was abandoned when a new palace designed on more European lines was built for the Nawabs in 1827.

Clive had left a dual system of finance in place with the Nawab's officials collecting the revenue and the Company's spending it, that proved unworkable in practice and offered enormous opportunity for corruption. The system was reformed and all power and revenue raising shifted downriver to Calcutta after 1770, and the Nawab was paid a stipend out of the revenues collected.

Fig. 3 Asaf al-Daula’s mosque at Lucknow

The two views of Lucknow, the Imambara (fig. 1) and its mosque (fig. 3), are possibly early works by the great Murshidabad artist Sita Ram, whose known and definite work was done under the patronage of Lord and Lady Hastings 1814-23. Sita Ram certainly used a charba of this drawing or another similar when he painted a view of the Imambara in 1814 (Losty 2015, pl. 65). His view also includes the great mosque beside it in a somewhat different manner to this Murshidabad view of the same mosque. Nonetheless, the towering presence of the mosque recalls Sita Ram's work in Delhi, particularly his views of the Jami Masjid and the quite small Kalan Masjid, where his low viewpoint imparts an imposing presence to the buildings (ibid., pls. 103, 106). The use of a tree along the side in the Murshidabad view of the mosque, a favourite device of Picturesque artists, also recalls the later work of Sita Ram who was very fond of it (ibid. pl. 34 for instance).

J.P Losty

Literature

Das, Neeta, and Llewellyn-Jones, Rosie, ed., Murshidabad: Forgotten Capital of Bengal, Marg Foundation, Mumbai, 2013

Llewellyn-Jones, R., ed., Lucknow Then and Now, Marg Publications, Bombay, 2003

Losty, J.P., Sita Ram: Picturesque Views of India - Lord Hastings's Journey from Calcutta to the Punjab, 1814-15, Roli Books, New Delhi, 2015 (co-published as Sita Ram's Painted Views of India, Thames & Hudson, London, 2015)

Markel, S., and Gude, T.B., India's Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow, Prestel Publishing, New York, 2010