What does sound look like? In pre-colonial north India, music scholars, poets, and painters developed images and descriptions for the musical entities known as ragas, and strung them together in a series or “garland” (mala). While it is not clear precisely when listeners began to conceive of music this way, by the 1500s, ragamala poetry and paintings were well established, and proved to be extremely popular until the nineteenth century.

Indian art musicians compose and improvise on the basis of raga, which is often translated as “mode”: a raga provides a defined set of notes, and the conventional sequences they should follow, so it shares aspects of a scale and a tune, but does not quite correlate with either. Raga was first theorised by music scholars writing in Sanskrit from around the eighth century, and over time it was explored in terms of dominant notes, melodic patterns, and signature motifs. Beyond these technical properties, each raga also carried emotional and aesthetic meanings: ragas have names, and over the centuries have been assigned genders, seasons, times of day, feelings and moods, colours and deities.

From the mid-fourteenth century, music treatises started to describe how to visualise ragas, beginning with the Sangitopanisat-saroddharah. The technique in this work closely followed a method of mental imaging used in meditation and tantric ritual known as dhyana. These early raga visualisations were similar to the iconographies of deities, detailing the number of heads and limbs of the raga’s body, its complexion, the colour of its clothing, and the animal it took as its vehicle:

Vasanta has six faces and ten hands, and is of the colour of coral. He carries cymbals, a conch, a skull-tipped staff, a fruit, a cakra wheel, and a lotus in his hands. Two hands hold a vina, and two grant beneficence and fearlessness with their gestures. He has a cuckoo as his vehicle, and he is sung in the months of caitra and vaishaka (1).

From this period onwards, the different ragas were arranged into clusters or families, typically involving six principal ragas and their associated raginis, who could be called their wives and children. Over time, the imagery evolved and became less godlike, as poets and painters increasingly turned their attention to depictions of human lovers, warriors, and sages instead.

Different systems emerged, each with its own sets of families and iconographies, so ragas could assume quite different forms. The folios in this collection are based on a system developed in 1570 by Ksemakarna, a musicologist from central India. It was traditionally thought that he worked for King Ramcand of Rewa, though new research by Ayesha Sheth suggests he was employed by the Gond court of Nripati Jatalendra at Hariyagarh. Ksemakarna’s ragamala sequence is especially elaborate, covering 84 musical entities, arranged into family units of 6 rāgas, their 5 wives, and 8 sons. While this system was taken up by upcountry painters based in the Pahari courts from the end of the seventeenth century onwards, the images in this collection suggest the ragamala was also circulating between the northern Deccan and Rajput courts.

While this kind of visualisation was originally explored in highly technical studies on music, verses from these esoteric works were copied and illustrated in courtly paintings and became a very popular subject in artists’ workshops. In the examples in this collection, the dhyana verse appears above the image: painters did not always follow these prescriptive verses to the letter, and schools of artists developed their own interpretative stance to each raga. The viewer of the painting could read the verse, imagine the vignette in their own mind, and then nuance that image by examining the painting. Looking at these paintings today, the silent partner in this exercise is the music itself, but in the courtly context these visualisations would stimulate conversations about the emotional and symbolic textures of musical sound. Courtly patrons and music lovers commissioned ragamala poems both as books and painted images, and often decorated their music rooms with wall paintings of ragas as well. To be taken seriously as a connoisseur, learning the different iconographies, timings, and emotional layers of each raga was a must.

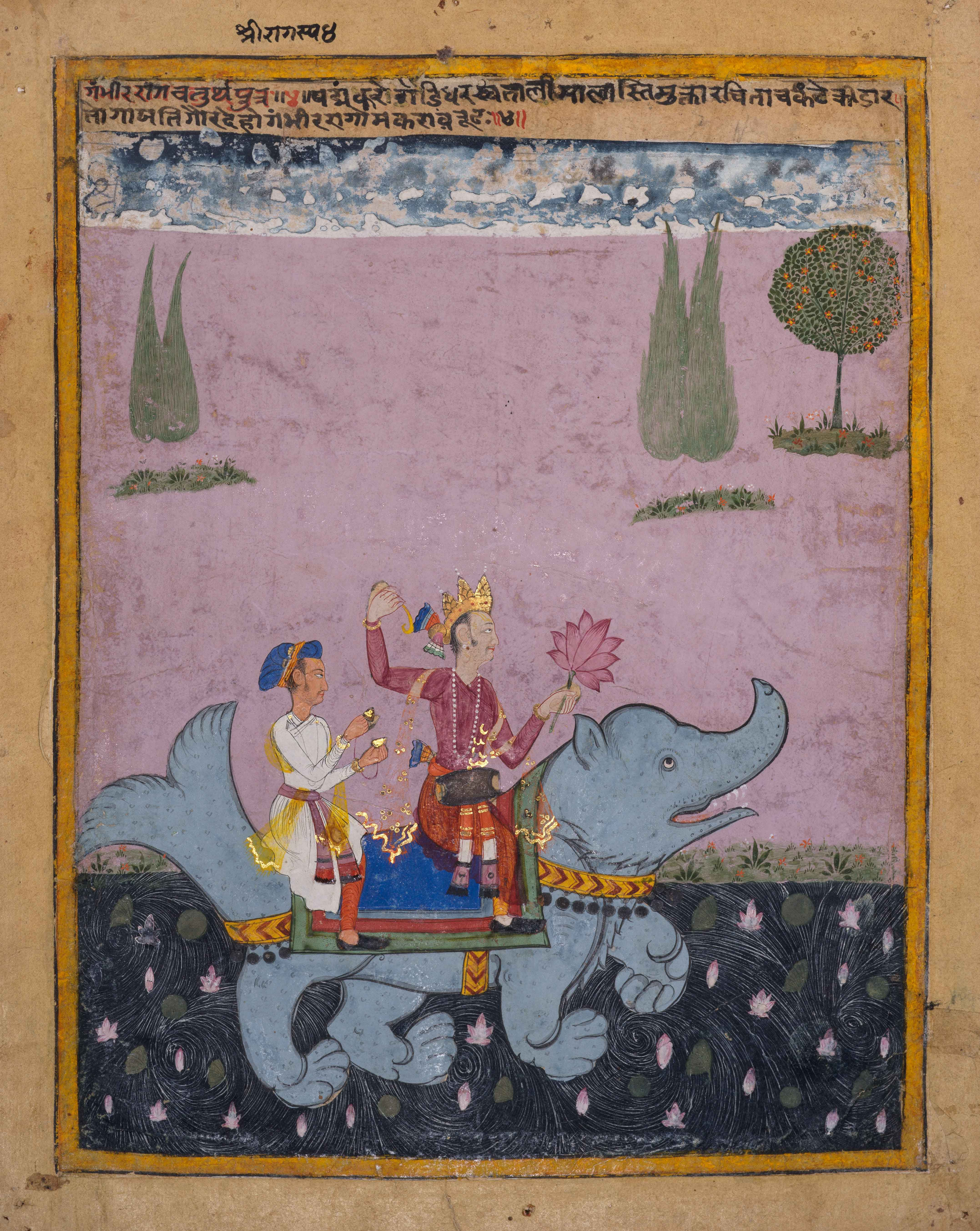

Fig.1

Fig.1

Gambhira putra, fourth 'son' of Sri Raga

From a dispersed Ragamala series, North Deccan, circa 1630-50

Poets and painters devised multiple methods for describing the layered meanings of a raga. The musicological approach was to dissect the raga’s formal, scalar properties: which notes to perform and emphasise, and which time of day and season to play or sing. In Ksemakarna’s ragamala, the ragas are also associated with other sounds in nature. For example, the treatise argues that raga Gambira (fig.1) stems from the sound of a sea creature called makara, an elephant-crocodile hybrid. The makara was a well-known feature in South and Southeast Asian temples, where it was believed to offer protection to shrines. The makara also had astrological significance, as it is equivalent to Capricorn in the Sanskrit zodiac. Gambira’s name literally suggests “depth”, as in a deep sea or a heavy, deep resonance. In the visualised image, the raga triumphantly rides the sea creature, embodying a spirit of play, ensconced in rhythms from the drum on his lap and his companion’s castanets. The rhythmic resonance of the raga seems to envelop the entire scene, as the dark waters swirl and spiral beneath him.

Vangala (Fig.2) is associated with the sounds of beans being ground down with a stone. However, the visual route was to focus on the dhyana: above the image of Vangala, the Sanskrit inscription tells us that the raga embodied a learned man, reciting the Vedic scriptures in a white garment, with a rosary and cup, who takes pleasure in conversation, dance, and song (2). Artists might go one step further, expanding on the prescribed image, exploring the emotional mood of the raga, and elaborating on the details to create a particularly poignant image. In this instance, the artists who worked on Vangala did not incorporate the wiseman’s love of dance and song (or the sound of beans!): instead, he is dressed as an ascetic, adorned with sectarian markings upon his brow and a tiger-skin stretched out beneath his meditating body. His fair body is entwined with a rosary, and his telling fingertips suggests that sacred chant is emanating from his lips, the ephemeral sound of his utterances contrasting with the heavy solidity of the building before him.

Fig. 2

Vangala raga, first son of Bhairava raga

From a dispersed Ragamala series, north Deccan, 1630-50

Under the Mughal Empire (1526-1857), the visualisations of raga continued to be described in Sanskrit and Classical Hindi, but also in Persian, the predominant language of Mughal intellectuals. Scholars of music were especially intrigued by the power of the ragas, which they learned about from reading older treatises and discussions with hereditary lineages of musicians, who passed on the tales about the ragas’ supernatural properties that they had inherited from their forefathers (3). Music makes an impression on us because a raga is aligned with the celestial bodies above and the elements and humours below: Megh (literally “Cloud”) could summon the rains or sooth its listeners, Dipak (“Flame”) was highly combustible, and could start fires or fevers, while Kedar, when performed correctly, could even melt stones.

Ragamala gradually fell out of fashion over the nineteenth century, partly because the aesthetic worlds of the Mughal ancien régime were denounced as decadent and effeminate in colonial India, and partly because approaches to musical interpretation were changing. While many of the associations about particular ragas persist in the musical imagination, professional artists today prefer not to be constrained by the iconographic definitions of ancient texts: musicians hope to convey their own emotions and images when they perform, rather than having to follow a template set by ragamala paintings.

However, the historical popularity of ragamala attests to the depths and pleasures of this genre, as intellectuals, poets, and painters grappled with the meaning and emotional weight of music, and translated it across media, languages, and images.

By Richard David Williams

Literature

1 Translation adapted from Allyn Miner, The Sangītopanisat-saroddharah (New Delhi: IGNCA and

Motilal Banarsidass, 1998), p. 93.

2 Klaus Ebeling, Ragamala Painting (Basel: Ravi Kumar, 1973), p. 72.

3 Katherine Butler Schofield, (2010). 'Reviving the Golden Age again: 'Classicization', Hindustani music and the Mughals,' Ethnomusicology 54:3 (2010), pp. 484-517.